Introduction

“A ship in harbor is safe, but that is not what ships are for.”

~ William G. T. Shedd, (1820-1894)

Vacation Boy Comes to Life

Bursting out of college with a desire to experience the world, my “career” began at Club Med in the Dominican Republic. We G.O.’s (Gentils Orginisateurs “nice organizers”) worked seven days a week taking care of the G.M.’s (Gentils Membres “nice guests”). As a tour guide, I was one of the few fortunate employees who could go beyond the walls of the resort, taking the G.M.s on exotic outings like 4×4 jeep trips into the mountains to see cacao and coffee fields or whale watching in Samana.

When I wasn’t occupied by my G.O. duties, I was free to take advantage of the resort facilities. I snorkeled, water skied, windsurfed, played tennis, and learned the trapeze. Between the trips I guided and the time I spent at other people’s stations, my envious fellow G.O.’s started jokingly calling me “G.M. Jon,” accusing me of always being on vacation. The nickname “Vacation Boy” ultimately stuck and became the email subject heading sent out to friends and family over the past 20 years to let them know I was still alive and catch them up on my goings on. At their urging, I collected these stories into this book.

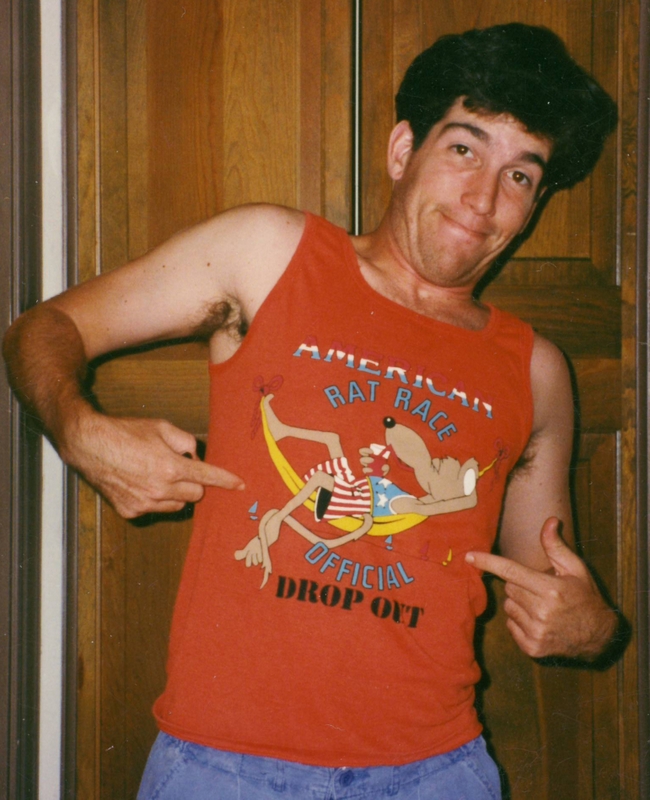

Jon just prior to embarking for Club Med where Vacation Boy came to life

Jon just prior to embarking for Club Med where Vacation Boy came to life

Japanese Love Hotels

A bawdy quest for academic enlightenment

While studying abroad in Japan—in the name of research—I ended up with a bloody gash in my head, which I hid to avoid having to explain what really happened. It’s time I finally reveal the details of this risqué misadventure inspired by a benign term paper assignment. If you are put off by descriptions of an explicit nature, you’d better skip to the next chapter.

Love Hotels are a curious spin-off of Japan’s live-with-your-extended-family-in-(sometimes-literally)-paper-thin-walled-house society, where privacy at home is all but nonexistent. These unapologetically tacky institutions for amorous interactions mushroom up even in extremely rural areas. A few typical characteristics: they are easy to spot as they are often shaped like castles or feature other randomly exotic architecture like a Statue of Liberty, and are not shy with their use of neon lighting. They often have foreign names like “Hotel Princess” or “Hotel Belle Amour.” Love Hotels rent rooms by the hour and are busiest during the day for affairs and other quick trysts. (Staying in one overnight can be a real bargain.)

Love Hotels specialize in privacy. The garage entrances usually have plastic drape flaps, which hide the people inside. Some have private garages for each room so you can go straight to the room without crossing a public garage. Payment is conducted privately through special wall panels below face level and more recently even with pneumatic tubes like a bank drive-through. They are known to have oversized bathrooms, cable radio with many stations, and any number of other sex-oriented eccentricities. Some have special theme rooms like “classroom,” “jungle,” “jail” or “spaceship.”

I learned this doing my term paper for my Japanese language class at Nanzan University in Nagoya during my year abroad in college. Instead of writing about traditional topics like “Tea Ceremony” or “Ikebana” (flower arranging), I decided to research something that actually interested me. I was curious to know more about these mysterious, secretive institutions scattered all over Japan.

I did my research through interviews with Japanese people, in-the-know foreigners, and later via in-person visits (not what you are thinking!). Much of my firsthand research came from observations of the buildings’ exteriors, going hotel to hotel photographing them for my eventual slide presentation. My buddy Rob, a gaijin (foreigner) friend of mine with a decent camera, accompanied me in this fun adventure. We got plenty of pictures from the outside, but—notoriously press-averse—none of the hotel personnel would let us in to photograph the interior of a room. Some told us to go away via intercom even before we got to the part about asking to be let inside. I’ve heard a number of these hotels allow female couples in, but not male ones, which is what they must have thought us to be.

My presentation date was drawing close, and after visiting maybe 30 hotels and not being let in to any of them, it was time to be more proactive. I talked a female gaijin friend of mine, Maria, into taking off from school during our lunch break to visit a place I had seen offering a “30-Minute Special” for $15. I was a poor student and that was still a lot of money for me, but I figured it would be worth it, knowing the legitimacy it would add to my report––not to mention satisfying my own curiosity.

We got there and into a room with no problem, on the way stopping to grab some bread things—as only Japanese bakeries can dream up—for lunch. Once in the room, I was delighted to be able to photographically confirm many of the features I had heard so much about: nice large bathrooms, cable radio, and many mirrors. I got a great picture of me on the bed demonstrating the ceiling mirror.

It was only when we sat down for lunch and I was completely out of film that I came across the thing I had been hoping to photograph most: the much talked about room service menu for sexual toys, whose titillating pictures made it graphically clear that dessert could come in many forms. In the interest of academic integrity I decided to take it home with me, photograph it, and then mail it back. (You may still be wondering where the head injury comes in.)

By the time we finished eating lunch, our 30 minutes were up. We called down to the reception to send up someone to collect the money through the no-see sliding pay window next to the door. When the window slid open, an elderly woman’s voice politely said, “That will be $45, please.” Taken aback, we explained we were here for the 30-minute special. She responded that the special was only for Sundays and holidays. There was no way for us to pay that amount, so she went to get her manager.

When he arrived, we had to open the regular door and uncomfortably speak with him face to face. I let my much-more-blond, much-more-female, much-more-fluent-in-Japanese counterpart be the lead negotiator. After some wheeling and dealing, we settled on about $25 after confirming we had not used the bath area.

As we headed out the door and down the stairs, the manager entered the room, apparently to inspect it. Three thoughts rose up in my mind in succession:

“Uh oh, I hope he doesn’t get worked up about the crumbs we dropped from lunch.”

“Uh oh, what about the comb and other…um…disposable amenities Maria had pocketed?”

My pace quickened with each thought but then…

“OH SHIT, THE DILDO MENU!”

Maria and I were whispering these observations to each other as they surfaced in stream of consciousness. As we descended faster and faster, a timer was ticking in my head, playing through the imagined movements of the manager as he inspected the room. I calculated we still had some time and encouraged Maria to walk out at a normal pace to not arouse further suspicions. Probably not destined for a career as a criminal, as soon as we got to the reception/parking garage (and likely under the watchful eye of security cameras), Maria started to run. At that point I could only do the same.

As we sprinted through the garage entryway’s plastic privacy flaps and up the quiet neighborhood street, the timer in my head was counting the seconds and determined we were not going to make it to the corner before the manager or someone else could potentially come out after us. We ducked into the grounds of a small temple, hoping to cut through the block. Unfortunately, there was a sizable wall between the temple and the next property over. We decided to climb over the wall and scoot out the other side.

I went first and, in the heat of the moment, did not pay sufficient attention to the clearance of a tiled roof overhanging the wall. When I jumped up, my head smashed on one of those (very hard) round tiles that abut the end of a roof. I dropped back down feeling “not so good.” We decided to ditch the over-the-wall escape and, after confirming the coast was clear, went for the nonchalant walk away approach.

It was only once we were safely around the corner and almost to the subway that I touched my aching head and came down with a hand covered in blood. I had a pretty good-sized gash. Maria was concerned I had suffered a concussion.

We were on our hour’s lunch break from school, so we had to hurry back to campus. Maria slid into class while I made an unavoidable stop at the school clinic. I didn’t get stitches, but ended up with a sizable tension bandage crowning my head. I stupidly wore a baseball cap even indoors for several days, not knowing a decent way to explain to my Japanese host family what had happened.

Smiles of shock and awe is the best way to describe how my presentation was received at school. It was a fun presentation to give, although challenging to keep a straight face and serious demeanor, especially when some of the racier pictures flashed up, evoking gasps of laughter. Knowing the stories behind how it all came together made it that much more amusing for me. Ahh to be a student again…

Mosquitoes, Chickens and Tarantulas

Fun on the Dominican Republic’s Chavon River

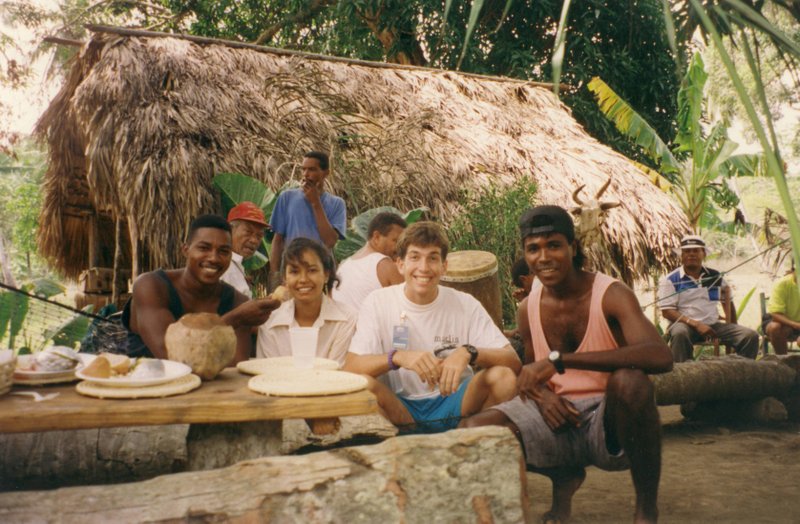

At last, I was on vacation. After taking care of guests seven days a week with no days off for six months straight at the Punta Cana resort, my Club Med career had concluded. I came to Bayaibe, a sleepy Caribbean fishing village in the southeast corner of the Dominican Republic, to begin a vacation I could call my own.

Bayaibe was the kind of town where sandy dogs lazed under the shade of breezy coconut trees, and it was difficult to break a 100 peso bill (about $8) because stores didn’t have change for a bill that big. The town served as the kickoff point for boat tours heading down the coast to visit some of the most amazing beaches I’ve ever seen, eventually ending at the tropical outcrop of Saona. As a Club Med tour guide, I took guests out to that paradise regularly. Bayaibe was also the staging point for a different tour we did on zodiac boats, which traveled up the nearby jungle-lined Chavon River. Many of the locals who worked on both boat tours lived in or near Bayaibe.

I had come here to meet up with the French couple who ran the zodiac tours, Chantal and Christophe. They were building a thatch-roof bungalow in a bend in the dark green Chavon River. This is the river that was used in filming some of the final scenes of Apocalypse Now. During the course of the season, I had become friends with them and their crew and was looking forward to some down time when we were not on the clock.

I had come here to meet up with the French couple who ran the zodiac tours, Chantal and Christophe. They were building a thatch-roof bungalow in a bend in the dark green Chavon River. This is the river that was used in filming some of the final scenes of Apocalypse Now. During the course of the season, I had become friends with them and their crew and was looking forward to some down time when we were not on the clock.

“Not on the clock” was definitely a good way to describe my new status. Relying on the imprecise communication method of posting notes at a central point in town to let Chantal know I was there, I spent the day hanging out on a beach near Bayaibe relaxing and trying to grasp the idea that I was no longer working, and hopefully would not be for at least another several months.

With no sign of Chantal by nightfall, I realized I would have to stay the night. Luckily I encountered a couple people I knew as staff on the boats from my Club Med trips, and we went out to the only bar in town to cavort with other Bayaibans.

I got schooled in billiards by a young pool shark, who could barely see over the side of the table. I had impressed myself by clearing all but two balls right out of the opening break—my best pool streak ever. This kid’s older friend then said in a slow deep voice, “OK, stand back, watch and learn,” before the 12-year-old cleared the entire table in one go. He was incredible. His movements were effortlessly quick and smooth. Sometimes I felt he wasn’t even looking at the table. The Canadian bartender Pierre summed it up saying, “If it is for work, they don’t try too hard, but they will go all out to learn how to play a game well. Ever see them play baseball?”

I spent my first night of this long-awaited vacation offering myself as a gratuitous buffet to the resident mosquitoes. After futilely trying to duck the hovering mosquitoes throughout the night using the classic hide-under-the-sheet defense, my false hopes of a lazy sleep-in morning were shattered time and again starting around 4:30am when I was repeatedly awakened by the Bayaibe Chicken Tabernacle Choir. Those damn birds sounded as if they were perched directly around my bed. One chicken would cluck, another would squawk, and before I knew it every chicken in town was crowing at the top of its lungs. They would settle down, pause, and just as I was drifting off to sleep, start the whole thing over again. Ugh.

One of the boat captains I was hanging out with the night before, Carlos, woke me up for real at 7:30am so we could meet our ride to the river to rejoin Chantal and company. A group was coming from Club Med, so I would have a chance to see what the Zodiac Safari I had been leading looked like from the other side. We piled into a pickup deathtrap with food, ice, an outboard motor and other supplies needed for the tour and headed for the put-in spot on the river above the spillway.

The fact this truck could run at all was a feat of non-modern ingenuity. The driver had to use a pin to keep the cab door shut. The gas was being fed via a hose to the motor from a jug under his feet. The brakes would best be described as coaster brakes because he would press the pedal down all the way and then we’d gently glide to a stop. Supposedly, at one point this vehicle had broken in two and the guy managed to put it back together enough to drive it. On the way to the river, it died twice. His method for curing this ailment was to pound on the motor with a hammer for awhile until it miraculously came back to life.

On the way we picked up a couple more of the zodiac captains and the zodiac boats themselves before finally making it to the river––thankfully alive––where we caught up with Chantal and Christophe. When asked later why, pray tell, she trusted her operation to this guy’s driving services, Chantal responded with refined Dominican practicality that he was still more reliable than any of the other guys with better trucks.

Some of my coworkers from Club Med came with the guests to try out the excursion, so I went along for the regular morning portion of the tour to spend time with them. After lunch, though, it was a wonderful sense of freedom to stay and hang out with the local staff rather than continuing on with the group. It was a pleasure making the beans for the next day’s excursion with the lovely Laila, the curly-haired beauty who assisted with the tours.

In the evening, we all piled into a zodiac for a dusk cruise to the site where Chantal and Christophe were working on their future home. The river and its valley are magnificently calm at night. We passed the tree where all the cattle egrets in the area come to roost. It looked like a Christmas tree overly weighted down with bright white ornaments. Once back to the ranch, we stretched a fishing net across the river in hopes of catching something overnight.

Chantal’s future house still had a long way to go. At this point, there were the beginnings of a frame, meaning a few palm columns stuck in the ground, surrounded by a field full of drying cana fronds that would later become the roof. Chantal and Christophe had been staying on site in a tent for the last several days. They managed to cobble together a cot for me with a mosquito net over the top. Good enough for me, although I didn’t end up using it that night.

Before settling in, I journeyed up the mountain trail to El Gato, the village perched at the top of the hill where Laila and a couple other zodiac guys lived. On the way up, my flashlight beam crossed paths with a couple fuzzy black tarantulas, which were bigger than my hand with all the fingers spread. And one of those poisonous, horror movie clichés was right next to my foot! I became WAY more careful where I stepped.

Arriving in El Gato, I felt I had superpowers as there was no electricity and most people simply walked around in the dark or used candles or weak gas lamps. My flashlight was like a lighthouse, the brightest thing in town.

Laila was being friendlier than her ordinary shy self. We stopped by a couple candlelit stores before heading to her place for dinner. We dined on the gourmet delicacies of Chef Boyardee lasagna, then settled into a conversation between me, Laila, her inanimate brother, and later also her drunk cousin Domingo. Domingo came stumbling in, hinting I should marry Laila so she could get a U.S. passport, a suggestion which somehow didn’t come as a surprise. I made the fatal mistake of declaring I didn’t see myself as the marrying type. Good thinking, Vacation Boy. Laila hardly spoke to me after that. Sigh.

Oblivious, drunk Domingo was proud to be showing me the life of a campesino (country person). He and I kept the incoherent conversation going well after Laila slipped away to go to sleep. He offered me his bed to sleep on while he tripped his way to the garage and passed out on a sofa.

Starting-to-sober Domingo stumbled in and out several times starting at 4:30 am on his way to the store to rekindle his buzz. He tried to get me to come with him, but I fended him off saying I was on vacation and wanted to sleep more. Laila came by at 7:00 am to wake me. She seemed annoyed I wanted to sleep in. There seems to be some kind of country ethic there that even if you don’t have anything to do all day, you still have to get up early. I think I was the last person to wake up in all of El Gato.

I got up and was headed back down the mountain when Domingo spotted me from the store and came running over to give me a big, happy alcoholic hug. Apparently he never made it to his field where he first suggested he would be out working. After turning down several beer offers, I headed down to the river where the fishing net had already been hauled in. Dang, I was hoping to see how that went.

Many Club Meds have a Circus area where guests can learn the trapeze, juggling, etc., including the one where I worked in Punta Cana. The combination of a newfound love for trapeze, and the fun people running it, made the Circus Team’s area one of my favorite places to hang out in my free time at the Club.

On this morning, the Circus Team was coming to me. That entire team and some other friends came on the first-ever all-GO zodiac trip as sort of an end-of-the-season party. Once GO’s get out of the resort village walls—where most of them have been cooped up for months—things can get crazy and this day was no exception. Even before the first ten water fights, everyone was hammered and some of them even made it a clothing-optional trip. When we got to the swinging vine—a favorite stop on any tour—the circus team showed their true form, even pulling off double backward somersaults. I choked up a bit seeing them go at the end of the day as some of us had become like brothers working together all that time.

That night I collapsed into my rope cot by the river where yet another fitful night of sleep awaited me. Chantal’s nervous dogs were new to being by the river and would go berserk at the drop of the hat, which included cows and horses moseying across the “house,” or every time the machete-strapped not-terribly-bright watchman wandered up from the river to check on things.

In the middle of the night, the watchman started building a big fire right next to me.

“Why (on Earth) are you doing that?” I asked.

“Christophe told me to make some coffee for them at 7:00.”

“OK, but why are you doing this at 5:30??”

“Oh, oh yeah.”

He went to do something else for awhile.

At least this morning I was in time to help the watchman haul in the net we had again set the night before. We caught a few good-sized but real ugly fish. Chantal gave a couple of them away, but I cleaned the one that looked the most edible.

Breakfast was an adventure unto itself. We began by paying a visit to the farm downriver where we got fresh eggs and an even fresher chicken—still alive and clucking when we brought it back to camp. A local guy dropped a bowl of fresh honey and honeycombs he had acquired by smoking the bees out himself. It was so good!

Struggling to get the potatoes and eggs cooked over a difficult fire, it was early afternoon before we finally tore into the absolutely delicious omelet Christophe and Chantal had prepared. All along, they joked about how bad/slow the service was for their one client at their soon-to-be-world-famous restaurant.

Next we had the fish, which we had prepared “Tahitian style”–uncooked but marinated in lime juice and coconut milk. It was quite a tasty meal, but I was praying my body would take all this with good humor.

Cooking this meal with my friends forced me to confront my carnivorous eating habits head on. It is one thing to buy prepackaged Holly Farms’ safely Styrofoam-encased, attractively organized meat pieces at a Piggly Wiggly grocery store (yes, I am from the South). It is another thing entirely to carry a living chicken back from the farm where it grew up and then watch as its head is lopped off with a machete on a tree root and then flips and flutters around without its head spurting blood here and there. My thought is if you can’t witness something like that and be ready to eat it, you shouldn’t be eating meat in the first place. That said, I will admit freely it was the first time I had been privy to the killing of a chicken and, feeling squeamish, I was relieved when Christophe stepped up to be the machete man. Does that still make me a meat eating hypocrite?

Christophe and Chantal tried to convince me to stay longer, but I had other friends waiting for me in the capital, so they took me on one final zodiac ride and dropped me off close to the main road. Little did I know that on the hand I was waving goodbye with was a lifelong souvenir in the form of an innocent little red bump on my index finger. That dot later filled up with a soup of yellow and blue liquids, swelling my finger up to three times the size of my thumb. I suspect that painful unpleasantness originated from some sort of bite while sleeping by the river. The divot remains forever on my finger, and reminds me of otherwise pleasant memories of my time on the Chavon River.

Descending Mountains Without Shoes or Sobriety

From Colorado to Alaska

The story of why and how I ended up living a day’s drive from the Arctic Circle began in Colorado.

I had spent the winter working front desk at a condo complex at the foot of Colorado’s Beaver Creek ski resort, which neighbors world-famous Vail. As the Vail ski mountain season came to a close, my Colorado winter of 100+ glorious days of skiing came to a festive end.

Like resorts around the world, closing day traditions are almost religious in fervor as skiers celebrate the passing of another ski season. At Vail, locals traditionally gather at the top of the mountain where several chairlifts come together, then a giant party ensues involving beer, wine, champagne, etc. The party builds as the day advances, until the top is completely packed with skiers and snowboarders.

This particular spring day started with a fresh layer of snow on the ground, and more continued to dump through most of the afternoon. Locals who would have ordinarily focused all their efforts on partying were intermittently pulled away like cocaine junkies by the allure of the abundant white powder, only to regroup at the top later.

When the chairlifts at Vail finally stop running at the end of the day, there are two separate traditions. For one group, the cheers from the gathered crowd marking the stopping of the last lift is the starting gun for the wild and crazy “Chinese Downhill,” where a mass of (often inebriated) locals race to the bottom of the mountain all at once. Another group stays and parties at the top until Ski Patrol eventually shoos everyone off.

My pothead housemate Jeff had his own tradition. A long time resident of the area, Jeff prided himself on being the last person off the mountain on the last day of the season. This year he invited me to join him and a couple of buddies who often shared this tradition with him. Once the Chinese Downhillers were off on their zany descent and Ski Patrol began to kick people off the mountain top, we hid in the woods. Waiting for everyone to clear out, we imbibed another bottle or so of $4 champagne, as well as a collection of other less legal items. Giving Jeff’s special-occasion stash of shrooms a try pushed my normally more innocent self to an all time level of wastedness––on skis or off.

An hour or two later when we felt the coast was clear, we slipped out of our hiding place and I began the clumsiest descent of my ski career. Trying to get my legs to function normally was like herding cats. On steeper terrain, it was beyond me to link more than two turns together without falling over. Ordinarily a decent skier, I tried in vain to convince my legs to ski normally.

The slopes were completely vacant, an eerie feeling for a place that is usually mobbed. We didn’t rush down. Instead we stopped on occasion to savor the moment, crack jokes and appreciate the view.

When deciding how to descend, Jeff and his friends came up with the brilliant plan of skiing down under the Vista Bahn Express lift, something ordinarily off limits. Even these hardened veteran locals had never attempted this before. Tricky on even a sober day, the lift cuts a narrow line between trees through double black diamond expert terrain.

I would have been more worried if I wasn’t so busy laughing myself silly. I remember one brief moment of semi-lucidity, looking up at the chairlift suspended overhead, then down at the village as the light began to dim, pausing to pray I would get to the bottom without injuring or killing myself.

The light was transitioning from dusk to darkness when we arrived at the top of Pepi’s Face, a steep final descent into Vail Village where many world class races finish. Below we could see the ski patrol’s end-of-the-year party well under way on a deck outside their office. When they spotted us starting to come down the face, they all began to cheer us on. It was a glorious, albeit not entirely graceful exclamation point to the end of great season.

Alaska

From the moment the lifts stopped moving––and my vision cleared––I began to scan the horizon, looking for a destination where I could put my Japanese language skills to use before they rusted and fell off. Option #1 was to go work at a resort in the South Pacific. Option #2 was studying Aikido (a martial art) in Japan.

Pursuing Option #1 added significantly to my collection of rejection letters. I put off Option #2 for another time and instead decided on a third option: Alaska. Alaska has a high influx of Japanese tourists in the summer and seemed more convenient than Hawaii in that I could drive there.

Don’t let anyone kid you, Alaska is far. To give you some perspective, if you are driving from San Antonio, Texas to Anchorage, once you get to Seattle, you are only about half way. From Colorado, I made the “convenient” drive in exactly one week and two hours. I had no idea it would take that long. Along the way I got to see lots of frozen lakes, some bears, swarms of giant but slow-moving zombie mosquitoes, a bunch of moose (and signs warning there had already been a shocking 300+ moose kills by cars that winter alone), a fox, a wolf, a couple of huge bald eagles, and much more of the mostly flat and boring Yukon territory than I had ever hoped for. My car had a bad spark plug, which meant I could not drive over 25 MPH without the car stalling out and not restarting for at least ten minutes. It took a whole day of this monotony before I limped into White Horse, the capital of the Yukon Territory, the only city along the way with a car repair place.

While waiting for the repair shop to open in the morning, I ended up sharing a hotel room with a naïve, young Japanese guy who had been holed up there for several weeks. He had shown up there to kayak the Yukon River to its mouth, not knowing the river is usually frozen over around White Horse until at least late May. He seemed frighteningly lacking in provisions and planning for what would be a multi-month journey. I wonder if he ever made it.

Of the 3700 miles my odometer racked up, the most beautiful miles clicked off during the last stretch between Anchorage and Girdwood (easily one of the prettiest drives in America), where my journey came to an end. It would be tough to find a better place to end up. Just off Turnagain Arm and surrounded on the other three sides by mountains decorated with snow and glaciers cascading over the top, Girdwood is a gorgeous enclave about 40 miles south of Alaska’s biggest city, Anchorage, which Girdwood residents pronounced “town”.

Girdwood was home to famous skier Tommy Moe, about 1199 other people, some bears, even more moose, and some of the most eclectic cabin architecture you will ever see. Alaskans are proud of their independent nature (and the fact that if you divide Alaska in half, each half would STILL be bigger than Texas). In Girdwood they seemed to have gone out of their way to express their freedom through home construction. Funky colors and shapes abound in ways I never thought could appear on a singular city block.

Girdwood is a unique, incredibly scenic community which represents the best of small town Alaska. The people were very friendly. The only paved road is the one coming from the Seward Highway up to the Alyeska ski resort and on to the hotel. It is one of those places where after only a month and a half living there, I could go to either of the two bars in town and see at least someone, if not many people, I knew.

There is no home mail delivery in Girdwood and I loved the scene at the post office which consequently served as a social hub. Especially on colder days, people would leave their cars unlocked and running in the parking lot with dogs, kids or whatever inside to go check their post office box and say hi to whoever they knew inside. More people than not (myself included) were unable to get one of the coveted few PO boxes and received their mail via General Delivery.

Part of what made the summer so fun was sharing an apartment with my hilarious flightseeing pilot roommate Gary. With its 70’s sensibilities exemplified in its furnishings and shag carpet, we dubbed our apartment “the Lime Green Palace”. A bonus was that Gary’s boss occasionally let us borrow a plane to joyride around the area. With Prince William Sound and the Chugach Range—supposedly the highest concentration of glaciers in the world—at our doorstep, it made for stunning excursions indeed.

Before I got down to the business of working, I decided to treat myself. For my birthday, I went camping in Denali National Park, home to a bunch of grizzly bears and Denali, a.k.a. Mt. McKinley, the highest mountain in North America. This would have been a great idea, except it wasn’t—at least the way I went about it. In fact, my fiasco there goes on record officially as My Worst Camping Trip Ever. I am lucky I survived. What went wrong? A lot.

I started out in the Denali Park office where I was issued a bear box, a mandatory hard plastic shell for food storage, which ensures that if a grizzly decides to devour you, it will at least not get your food. I was also given some helpful information about hiking trail options, which almost proved fatal.

When asked about recommendations, the gal at the information desk told me in glowing terms about an area where she had camped two weeks earlier. It sounded perfect. The destination was a campsite that could be reached in less than a day’s hike with nice views of Denali from a relatively easy-to-access mountaintop. The only thing she and I did not realize is that it had snowed a couple feet there since her visit.

Most places in the massive Denali park do not have cut trails. You have to find your own way through the brambles, fields, streams, etc. just like the original explorers. Backcountry pass in hand, I drove in, loaded my backpack and began my hike up in the area the park ranger gal had described. It was not easy going. The bottom area was swamped with water, and as the climb began, the shrubbery seemed more intent on blocking my way than indicating a trail for me to follow.

I was hiking in the new Igloo brand boots my grandparents had given me for my birthday. In retrospect, I learned that Igloo needs to keep its focus on making beer coolers and not shoes. During my arduous upward swim through the brambles—I think because of being exposed to the mud and water earlier—the soles began to separate from the shoes they were very much meant to be attached to. No, this is not something you want when hiking through the Alaskan wilderness, especially when you are about to start climbing above the snow line, which is where I suddenly found myself. About three hours into my scramble, there was very-much-not-anticipated snow on the ground. Lots of it. My thought process was that Alaskans are tough, and when the girl had recommended this hike, there was no need for her to point out something so trivial as the fact that there was snow here because, DUH, this is ALASKA. As a newbie arriving fresh from “the Lower 48” as they call it, it was almost like Park Ranger Lisa was taunting me.

So I plodded along through the snow in my falling-apart shoes. As exhaustion began to set in, the higher I went the cold stiff wind only picked up its intensity. I already had to loop the laces of one of the boots around the sole to keep it from flapping completely open like a full-length trap door under my foot. The snow coming through the gaps did nothing to dry out my soaked-through sock.

It was hard to find a clear path to the top. At one point, I found myself scaling around a cliff where the frigid wind gusts were so strong they caught my backpack and almost spun me around sideways and off the ledge I was inching around.

In addition to cold and fear, I was getting tired. I had been at this slogfest for almost four hours and I was not near the summit nor close to anywhere I could set up my tent. I’ll be honest, I was starting to give up hope and was wondering if I would ever even make it down. It was at that low point that Mother Nature decided to give me a kick in the pants, in a good way. At a moment when I was pausing to rest and take in my situation, about 40 meters below me a bleach-white mountain goat gracefully skittered up to the top of a steep small peak below me, paused, and then scampered down the symmetric far side as easily as if it were on flat ground. It was the first sign of animal life I had seen since I began my climb. And then came another one. And then a third, and then another, all following the same precarious path. Seeing nature so gracefully in action and completely nonplussed by the harsh surroundings, was inspirational. I figured if they could do it, so could I.

The mountain goats cast a magic spell on me, bringing clarity to what I needed to do. I decided it was time to abandon hopes of making it to the top and instead focus on getting down to somewhere I could camp. I even slid down portions on my butt as it was easier than trying to walk down, especially with the state of my shoes.

The entire time during my hike, I had yet to see a single location suitable for pitching a tent. It was always too steep, too rocky, too covered with thick shrubbery or all of the above. Once below the snow line, pickings were still slim. I finally went with the best solution I could find, namely stuffing my tent into a gap in a rock cliff. It was by no means a perfect solution. The tent was still getting flapped about from the wind and the uneven rock floor wasn’t exactly a king’s mattress, but it was way better than anything else I had seen.

So then it was time for my birthday dinner. This was my first time camping in grizzly country and it had me on edge. I’d heard plenty of stories about the intelligence and ferociousness these magnificent beasts can bring to, ahem, bare. One thing you are drilled on before heading into bear country is how to prepare, eat and store your food. You are supposed to make a triangle, with your sleeping area in the upwind point, separating 100 feet between the downwind corners, which are used for food preparation and food storage respectively. You prepare and eat your food in one spot, store it suspended at the proper height between two trees in the second point, and sleep in the third––after changing out of the clothes you were eating in.

This is great in theory, but another thing entirely when you are trying to do it in inhospitable terrain and weather. I made my way out on a windswept rocky ledge to set up my stove and boil water. It was nowhere near 100 feet away from my tent, but it was the only place I could find to set it up. As I sat out there shivering, waiting for my water to come to a boil, I had visions of a hungry just-out-of-hibernation bear coming around the corner, finding me in the figurative (and perhaps literal) dead end of that rock outcrop as there was only one way out other than falling 50 feet off the side.

You would think that if the only culinary prowess I needed to prepare my freeze-dried meal was to boil water and pour it in the bag, someone turning 24 that day should have been able to pull it off. However, whether because of the altitude, or the gale-force wind, or the increasingly frigid temperatures, I could not get the water even close to boiling no matter how much I tried to shelter my poor struggling stove.

I gave up and poured the warmed water into my freeze-dried meal bag, hoping for the best. After waiting for the water to work its magic, I opened the bag to find chewy beef stroganoff chunks floating in a tepid bath of almost-salty water. They were barely transformed from the congealed dry powder they resembled prior to adding the water. I began gnawing my way through the watery amalgamation, singing to myself, somewhat ironically, “Happy birthday to me, Happy birthday to me…”. Even in my exhausted state, it was terrible and hard to get down. Lesson learned: truly boiling water is critical when preparing freeze-dried meals.

There was no good place to hang or place my food stores, so I broke one of bear country’s cardinal rules and left my bear box out there on the same ledge, hoping for the best. In the meantime it was time to finally bed down for the night. Yay. Only that didn’t go well either. Because I had no way to secure all the walls and doors of the tent, in the unrelenting wind the material FWAP, FWAP, FWAP, FWAPed like thunder all…night…long. As a silver lining, I figured the chaotic flapping about would at least discourage bears from poking their head in to dine on me during the night.

Not that it was easy to tell when it was night. Being way north this time of year it never got dark. It just got dim for awhile around 3:30 AM and then brightened back up again. I knew this because it was impossible to sleep.

Happy Birthday to meeee….Happy Birthday to meee…Happy Biiiirth…

At some point I decided it was morning enough to get up and head back to the bottom. I was glad to find my food stores intact. Along the way down, between the brambles and the water, one of my hiking shoes disintegrated completely and I found myself walking in the Alaskan wilderness wearing only a soaked sock on one of my feet. For all my trials and tribulations the day before, it thankfully only took me an hour to get back down to the blessed warm and dry sanctuary of my car.

So far I have yet to top this outing in terms of sheer misery, and I have had some doozies. What a way to treat myself on my birthday. Since then, though, when things aren’t going well when I am out camping, my mind drifts back to that night in Denali and I think, “Well, at least it’s not as bad as that was!”

Safely back in Girdwood, I took a waitering job at the stunning, almost brand spanking new Alyeska Prince Hotel, which was right there in the valley. It was Japanese owned and received quite a few Japanese guests considering how bleak the occupancy rate was otherwise. The employees referred to the place as “the Overlook,” the empty hotel in the horror movie The Shining. Before long, I was able to transition from waiting tables to the much more interesting position of concierge, which also gave me more contact with Japanese guests.

During Alaskan summers, there is plenty of daylight to go around. It is invigorating. Never is that more the case than Summer Solstice, the rarely-noticed footnote on most calendars every June 21st. In Alaska—where they spend so much of the year shrouded in darkness—Summer Solstice is a big deal. It is on par with the 4th of July. It is a time when people start a round of golf, or hike up mountains, or go skiing, or rafting or anything else outdoors—all in the bright sunshine at or around midnight. Some people drive closer to the Arctic Circle where they sit atop their Winnebegos drinking beer and watching the sun spin around in the sky without ever dropping below the horizon.

In Girdwood, there is an annual tradition to have a barn burner of a party up on Crow Pass, the rugged Girdwood “suburb” where to this day some people still subsist by panning for gold. I joined what was probably all the youth in the area for the giant bonfire, live music and lots of adult beverages. Some folks broke off around 2:00 am to hike up further to go snowboarding on a nearby glacier. How cool is that?

To this day, June 21st has garnered a special spot on my calendar. I think of the good people of Alaska and celebrate in distant solidarity the longest day of the year.

At the end of the summer, I switched to a job as a camping tour guide for Japanese tourists, taking them for hikes on Matanuska Glacier and up to Denali National Park. These went WAY better than my first trip there.

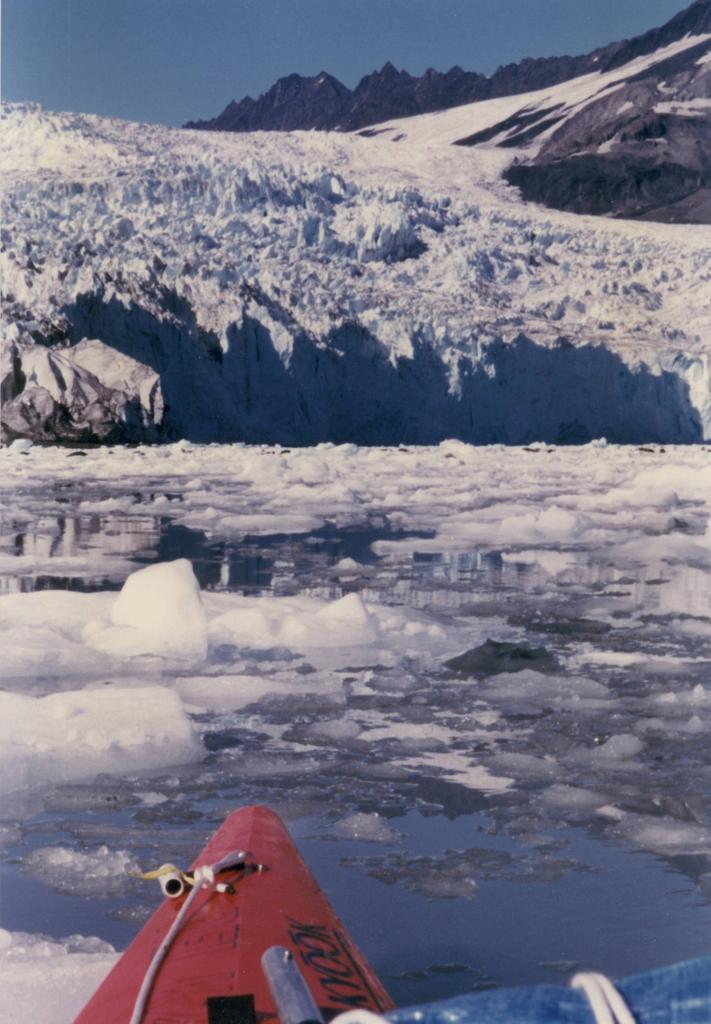

I ended up recruiting Kazu and Hiro from one of my groups to go sea kayaking with me in Harriman Fjord off Prince William Sound. After agreeing to join me for the multi-day wilderness journey, these young guys asked, “What is a sea kayak?” Hmmm. Maybe not the most solid partners for this level of adventure. They even wanted to see how I pumped gas at the gas station because in Japan everything is full service and they were planning to rent a vehicle and wanted to know how to pump it themselves.

Nevertheless, they were game for this four-day kayaking trip in the remote Alaskan wilds. And so we did it, surviving just barely.

I had been scoping out a possible trip to Harriman Fjord since flying over the spectacular glacial wonderland with Gary on a joyride flight over to Valdez and Cordova. This L-shaped fjord looked to be the most protected and prettiest area around, but it wasn’t an easy trip to sort out. No humans live nearby and it isn’t on the way to anywhere, so there is no regular means of transportation to access it. One sightseeing tour boat visited the fjord several times a week but it created more of a danger than a possible source of help. It wasn’t configured in a way for it to safely carry kayaks and it threw up a big dangerous wake on its way in and out, which could easily flip a kayaker into the icy waters. And when I say icy, I mean the kind of icy where even an Olympic swimmer would die in literally 10 minutes from the shock and exposure to the biting cold.

In Whittier we ended up hiring kayaks and crusty Captain Mike to run us out on his boat. Coming around the bend into the glassy water of Harriman Fjord took my breath away. With impressive mountains and glaciers plunging into the water, the fjord was every bit as glorious as I hoped it would be and more. Mike dropped us in what was the inside forearm of the bent arm of the fjord. When he shut down his buzzing motor to unload the kayaks and the gear, our own shuffling about and the sounds of the water gently lapping on the shoreline seemed offensively loud compared to the blissful silence beyond. Across from this magnificent campsite was an amphitheater as only Mother Nature could design, complete with its own built in thunder machine.

Glaciers, as it turns out, can be far from silent. Day or night, we would occasionally hear a distant echoing CRACK of the shifting ice, occasionally followed by the splash of newly minted icebergs collapsing into the ocean. We had to be wary of these icefalls when kayaking because when ice calves off, it can ignite a deadly mini-tsunami from the impact.

Once we got out and began exploring, we approached the glaciers from a cautious distance, weaving through the fields of ice floating in the water. The icy water had carved these mini-icebergs into interesting yet often dangerously sharp ice sculptures. Gliding amongst them, the noise of the water lapping up under ledges that had been eroded away sounded like a chorus of toothless seniors smacking their gums, but in a relaxing way. That sound was only interrupted by the gentle splash of the stroking paddle, the occasional clunk of ice hitting the kayak hull and sometimes less pleasant scraping noises when the hull glanced along frozen knife blades, making me wince.

The ice was a favorite hangout spot for seals and sea otters. With their expressive whiskery faces, fuzzy bodies, and tendency to enjoy playing when not snoozing on their backs in the water, sea otters should be legally declared the cutest animals on earth. Quite a few of them roam the waters of Harriman Fjord. They were curious what we were doing in their neck of the woods. They would pass nearby for a look when we were kayaking around and would occasionally swim by our campsite, kicking down strokes to lift themselves vertically higher out of the water to get a better peek at what we were up to. Adorable.

Rain began to sprinkle on the afternoon of the first day and only increased in intensity for the remainder of our four-day trip. Our campsite, with copious fresh blueberries and its stunning views of glaciers plummeting into the sea, started out as a scenic wonderland. As the days progressed, though, the paths and even the ground below us melted steadily into a river of mud.

We were fine when exploring the beauty of the fjord from the comfort of the kayaks, but life on land became miserable. With ropes, we jerry-rigged a kitchen under a rain poncho and oars. At one point I timed that we were able to fill a gallon jug of water from the runoff within ten minutes. My tent’s water repelling tenacity eventually gave out and a small pool formed down by my feet. Few of our things remained even remotely dry.

The water falling from the sky further ramped up its intensity. Instead of moving to a new campsite on the opposite side of the fjord for the third night as we had planned, we decided to remain where we were, knowing that if we tried to pack everything up and set it up again, things like sleeping bags that were not yet soaked through would be.

The final morning, while still appreciating the beauty of our surroundings, we were excited to know we would be getting out of there. We packed everything and began paddling over to the opposite side of the fjord to the place where we were supposed to have camped on the third night and where we had also set up the rendezvous with Mike, the boat captain.

But it took us longer to get there than we first anticipated, and well before were able to reach our destination, we heard the hum of Mike’s outboard motors coming into the fjord. Paddling faster now, we tried waving but we knew he didn’t see us as he continued on toward the original meeting spot. But he was still far from us.

Sensing the danger that we were about to be in if we did not connect with him, I urgently sent the Japanese guys sprinting to shore, instructing them to run up and down the beach shouting and waving while I continued to press on in the direction of the boat as fast as my arms would pull me.

Captain Mike pulled away from the second campsite and motored over to look for us at our original site. As he crossed over, it was clear he still had not seen us. He hovered on that shore for a bit, and then…he left, returning home. I could feel the hope draining from my heart as the boat picked up speed and the sound of the motor began to fade away from us out the mouth of the rain swept fjord.

But then something happened. I saw the boat slow, then stop, then turn around, then start to head right for us. We were saved!

It turned out that Mike’s girlfriend, Linda, had joined him for the ride out. At the last minute she was the one who spotted the Japanese guys frantically waving and running back and forth on the beach in their yellow rain ponchos. Phew.

Kiss on the cheek to Linda and the guardian angel that pointed her eyes toward us. One of the reasons they did not linger longer looking for us was because an Alaska-grade storm was fast approaching. The wet weather we had been experiencing was but polite foreplay compared to what was about to hit. In fact if Mike did not pick us up then, the severe weather would have prevented him from returning to get us for several days.

The rain and wind and resulting choppy seas made for a slow, arduous return to port. It was almost dark when we finally arrived. Mike found a dorm room of sorts for us to stay in and dry out for the night. The storm began to hit in earnest that evening. Watching the horizontal pouring rain from the dry dorm room window brought a sense of relief that is hard to describe, especially knowing how close we had been to being stuck in that maelstrom for days with dwindling food supplies and nothing dry anywhere.

Despite the near tragic ending to this trip, Harriman Fjord still evokes a longing in me. I hope one day to return to and explore its extraordinary beauty again…when it’s SUNNY.

“Get Down Here!”

An Insider’s View of the Atlanta Olympics and Bombing

Aside from the RVs and busses choking the roads and the mosquitoes, which are known to have carried off small children, the only real drawback to Alaska was the inevitable event creeping up on the calendar: winter. I never had any intention of avoiding the un-esteemed, undignified, derisive title of “fair-weather Alaskan”. As Jimmy Buffett so eloquently put it, “I gotta go where there ain’t any snow; I gotta go where it’s warm!” Knowing another winter of beaches and bathing suits would suit this warm-blooded sun worshiper just fine, I set sail for…Hawaii!

I got my bus driver’s license the winter of 1996 on the island of Maui. I bet my parents beamed with pride every time they told friends that their college graduate son was a bus driver. Over the course of that winter, I carted over 1000 Japanese tourists to their hotels and later back to the airport, checking them in at either end. I got pretty good at spotting whales while driving along the ocean. It became a source of pride that I could almost always locate them before my passengers did, despite the fact I was the one driving the bus.

I also got good at spotting roaches––in the bus—at least in one badly infested bus the company kept assigning me. It was horrible. Every day I complained vehemently on the sheet we had to turn in about the state of the vehicle, but these complaints fell on deaf ears. Finally, to get my point across, I squashed about 17 roaches with the daily sheet and turned it in without writing anything other than “(roaches)” on the sheet. Some of them were still twitching and waving tentacles on the paper when I walked out. The next day my boss sat me down for a tete-a-tete saying how inappropriate my actions were, but I somehow never got assigned that bus again.

Bus roaches aside, I loved that winter on Maui. I finally figured out how to do a windsurfing water start. My regular surfing improved considerably as well. It got to the point that I would start feeling ill at ease if I didn’t get in the water at least once every few days.

My Hawaiian life ended abruptly when I got a message on my answering machine asking me to come work in Atlanta for the Olympics. This phone call was from a woman, Eiko Mishima, who I had met years before when working as an usher at a Japanese jazz band concert at the University of Southern California, my alma mater. Mishima-san and I struck up a conversation while the concert was going on. It turned out she was from the Los Angeles office of the Japanese publishing company sponsoring the event. She was impressed by my Japanese and suggested we keep in touch. Over the years I did just that, meeting her on occasion for lunch when passing through LA. It just seemed like something I should do, although I was never sure why at the time. It turns out that jazz concert ushering job was the domino that set off a remarkable chain of events in my life.

Since I’d been looking to break out of my pattern of entry-level hospitality/tourism work, the decision to leave and go work at the Olympics was easy and immediate. As much as I enjoyed my time in Maui, I was moved out of my Hawaiian life within three weeks––rid of my job, my apartment, my car—and saddest of all—my surfboard.

In Atlanta, life started at a pleasant trot. By late May it took off running. I was working for a Japanese daily sports newspaper. It was an exciting job, especially compared to continuously pointing out the same dang pineapple field for five months in Hawaii. I started by helping set up the newspaper’s office operations. The main office was near an Atlanta commercial hub, Lennox Mall. Later we also had an office in the Main Olympic Press Center, plus an office by Stone Mountain where we printed 10,000 copies of the paper in Japanese to distribute around Atlanta and to other parts of the country. I also wore a reporter’s hat, doing reporting and photography leading up to the Games, including covering the US Track and Field Trials.

One specific event during the lead up to the Games formed another life changing link in that same chain of events I mentioned earlier. That day, a lot was going on in town and the main photographers were occupied elsewhere, so I was tapped to be the photographer for a leg of the Olympic Torch Relay where Tokio, a famous (in Japan) band was running.

The next thing I knew, I found myself standing in the dark along a middle-of-nowhere country road, at 5 a.m., groggy and wondering if we were in the right place as there was no one around for miles. If anyone would have told me a mini-career would be spawned from this moment, I would have been certain they were off their rocker. But in hindsight I can see the minivan eventually pulling up across the lonely road and the Japanese businessmen getting out, smoking cigarettes and chatting. I went over to say hello and see if they were confident about this being the right location as I was only going to have one shot at this important picture.

I spoke mostly to the shorter guy in the group, who years later would end up slapping me hard across the face in a mistaken drunken rage. But that was later. Oblivious to that future, my ears perked up upon learning they were from Coca-Cola Japan and were there because they had sponsored the band/runners’ trip. I mentioned I had been planning to go to Japan in the fall to try and find work relating to the upcoming winter Olympics, and that Coca-Cola was at the top of my list to call on. He maintained they only had a small office and not much promise for work, but I asked him to at least look for me when I came knocking on their door. Indeed he did. But that was also later.

For now, urgency shifted to the horizon where the arriving Torch Relay caravan lit up the night. I was given instructions from my Japanese reporter colleague to not be afraid to elbow my way through the inevitable onslaught of Japanese media that would be arriving to cover this event.

Everything happened so fast. All I remember was taking some pictures as one band member passed on the flame to his other band member and then I ran with the second one a bit, taking more pictures as we went––backup in case I had blown any of the previous precious pictures. I guess I did OK as my pictures ended up taking the better part of a page in the newspaper when it went to print later that day.

Back in Atlanta, once the Olympics began, my role shifted to being a driver/escort for a famous Japanese photographer. Not that any American (myself included) would have ever heard of him, but in Japan he is revered and as well known as George Lucas is in the U.S. I took him to practice sessions of the athletes as well as into the actual Olympic events. He didn’t have an official photographer’s pass, so we would often get chased off. We worked out routines where he would shoot like crazy while I delayed security guards as long as possible. VERY coincidentally, years later when travelling in New Zealand I caught a TV show about a security guard who had volunteered to work security at the Atlanta Olympics and sure enough, part of the footage showed him chasing off my photographer.

One undercurrent during the entire Olympics was watching my boss slowly become insane. Literally. He felt under extreme pressure to get everything right and his way of reacting to the pressure was to double up on his cigarette intake and halve his nightly sleep to less than four hours most nights. He never got more than four and a half hours of sleep a night over more than a three week stretch. His losing it resulted in longer and longer rants where, wreaking of cigarettes, he yelled at me, spattering spit, and going on and on about who knows what.

These one-way halitosis blasts eventually lasted 45 minutes or more where I would mostly nod and apologize and try to figure out some way to change the subject or get out of there. During one volcanic venting session he even suggested the only thing protecting me was that the VIP photographer in my charge adored me and loved the work I was doing for him. This happened to be my only responsibility. He hinted he was jealous I was getting to escort this famous guy around to nice restaurants and Olympic events, while he could only sit there and implode from fatigue.

My boss’s lack of sleep and instability got a real workout the night of the bomb. That evening, sometime after 1 a.m. I had been catching up with an old friend at a restaurant in the suburbs when we noticed on TV there was some sort of panic going on in downtown Atlanta. A bomb blast had occurred in Centennial Olympic Park, right at the heart of the Games, and directly next door to the Main Press Center where our office was located. I called my boss to let him know about it. Clearly already at the helm of this for a while before I called, in a completely exasperated and horse voice he screamed into the phone as best he could at that point, “What are you doing? GET DOWN HERE!!” And hung up.

I left my friend and jumped into my dad’s Acura Legend, which I had borrowed for the summer, and started streaking into town. At 105 MPH, cops were passing me left and right. Once I got into downtown Atlanta, I knew it would be impossible to get to the Main Press Center by car, so I ditched the Acura in a random parking lot and proceeded by foot. It was an eerie, confusing scene with police everywhere, police tape blocking off possible evidence, and many streets blocked off altogether. I spotted people walking away from the scene, visibly in shock, with blood on them. I gathered what information I could and snuck into the Press Center, which had been otherwise barricaded. The rest of the night was a blur of information, misinformation and press conferences. Over 100 people were injured, one woman was killed by the bomb directly, and a Turkish journalist died of a heart attack running to cover the story. It is a miracle my boss didn’t end up with a similar obituary.

In the end, this summer stint was a great job. My exposure to the in-the-trenches world of the media and other facets surrounding a humongous event like the Olympics was a major eye opener and as an Olympics junkie, it was cool seeing a bunch of events in person including a number of track and field world records.

<><><><><><><><><>

Within days after the Games were over, I was on my way to Alaska to work and play for a month. I returned to work for the same tour company I had worked for at the end of last summer, leading Japanese guests on multi-day camping trips. Between trips, I did trips of my own, including a five-day sea kayaking trip through the stunning Kenai fjords where I FINALLY caught my first real Alaskan fish and saw my first bear while camping—at the same time!

I was convinced I would be selling my car and shipping all my goods back to South Carolina before I left, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it, so I ended up storing things with a friend before taking off. Alaska is hard to give up (at least the summer part). Mind you, this return to Alaska marked the first time I ever returned anywhere I had already lived previously. With repetition like this in my life, the next thing you know I’ll have a wife, a house in the burbs, some kids, and a dog by my side. OK, stop laughing.

<><><><><><><><><>

Drunks Falling off Horses and Fun with Chicken Busses

Travels through Guatemala

Studying Spanish in Guatemala was something I’d had in the back of my head for quite some time, ever since my former math teacher Joy Ingham had told me about having done it herself. I finally had the funds and the time. I spent seven weeks living with three different families, studying Spanish at various schools. I studied entirely in Spanish with a private instructor four to seven hours a day. It was amazing how cheap this was to do.

I used my weekends to get out and explore the country with my newly made friends. Anytime I left the relative security of my Spanish lessons, I, like all Guatemalans, was subjected to the horrible “chicken busses” that roam the countryside. Almost every bus in Guatemala is an old American “Blue Bird” school bus, most of which were probably no longer considered roadworthy enough to transport America’s elementary school children.

They all share some common characteristics. Most importantly, they contain some kind of stereo cranking out a Latin mix of music well beyond the volume capacity of the cheap speakers. The driver is protected in the front by a collection of stickers containing the words “God”, “Jesus”, “Love” and “has blessed this bus” in various combinations and orders, sometimes in numbers to the point of blocking the driver’s view. Part of the mandatory maintenance program seems to require the removal of various parts of the muffler so as to be able to make the most noise as possible while belching out the maximum output of smoke. As they cram up to four adults into the space originally intended for two young children, all of these busses are filled to at least double the legal capacity, which is diligently posted right next to the sticker above the sun visor saying, “Looking out for the safety of your children”. But this is the only real way to get around (other than in the back of pickup trucks) and everyone in them suffers equally, except for the people located directly next to the pukers, of which there are many.

On one of these weekend trips, three of my fellow Spanish language students and I hiked up the 3742m (12,000ft) Santa Maria volcano. While well off the beaten path, we had heard it was a hike worth doing so we grabbed a makeshift tent, some warm clothes, a few cans of food and went for it. Ironically the highlight of the excursion for me was throwing up.

[…The story continues in the book Vacation Boy: Does This Count as a Career?…]

Thanks for one’s marvelous posting! I actually enjoyed reading

it, you are a great author.I will ensure that I bookmark your blog and will often come back later in life.

I want to encourage that you continue your great posts, have a nice evening!